The Lead (Pb) Data Initiative

A multi-stakeholder effort addressing environmental lead exposure and lead poisoning prevention.

This initiative is currently in an early-stage exploration and growth phase. Concepts include: Predictive analytics for local health departments, distributed and low-cost technologies to equip concerned citizens, and community building within and across select cities.

Initiative Details

Over the course of 6 to 9 months (starting August 2018), this initiative aims to:

Understand the landscape of conversations and activities already active across the country.

Work with city and county Public Health Departments to better understand barriers they face and to help upgrade their lead monitoring programs to incorporate new technologies and approaches.

Identify and test models of community engagement for the testing of lead in homes and public buildings;

Explore the development of a low-cost lead technologies to better equip community scientists and neighborhoods most at risk of lead of exposure;

Cultivate partnerships across communities: Colleges, Universities, Employers, Regional Foundations, Health Care providers, others; and

Pilot deep-dive multi-stakeholder conversations and data-sharing/gathering approaches within up to five (5) communities.

If early piloting is found to be successful, we would formally launch the Lead Data Collaborative as a multi-city coalition of community scientists, technologists, and public health advocates working together to collect and share data on lead exposure, enhance the low-cost tools for detection and remediation, and advocate for small- and large-scale remediation efforts.

Background

Lead is bad. And it’s (still) everywhere.

Lead is a silent, persistent environmental toxin. It can’t be seen, smelled, or tasted. Yet studies show that it is inherently unsafe at any exposure, with even miniscule amounts causing irreversible health impacts, especially in the neurological development of children.

Despite the substantial news coverage of Flint, and compared to other public health campaigns (e.g. mercury in fish), most Americans remain largely unaware of the large amounts of lead in urban environments. And because it is expensive to both test for the presence of lead and remediate issues when they are found, there has been little proactive action by public officials and continued public surprise about lead exposure when testing is done.

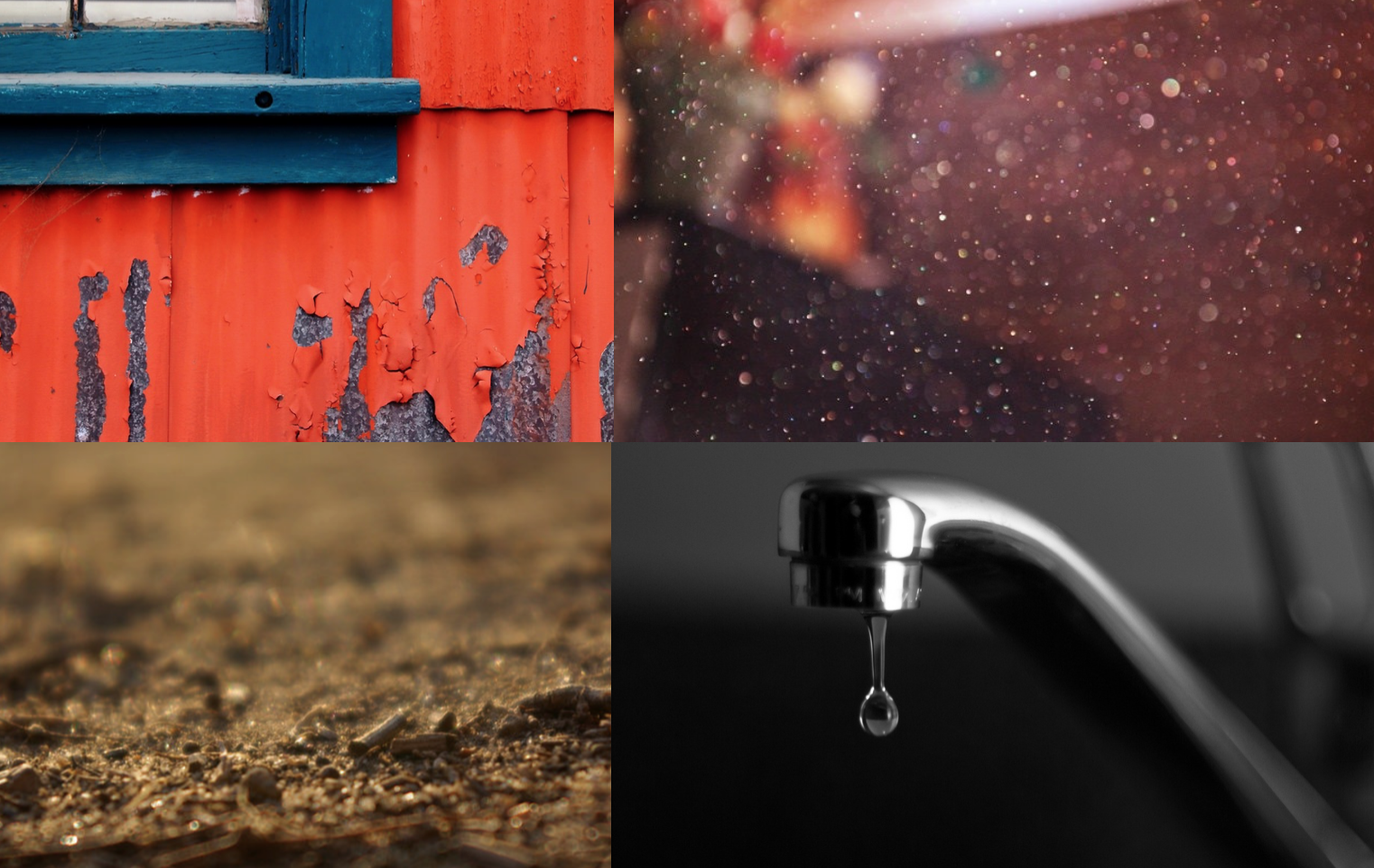

While lead as a public health issue has decreased significantly over the last 30 years, widespread use in the prior decades made lead ubiquitous in our lives. It’s still present in paint on older homes, soil where industrial and emission pollutants have settled, dust created by paint and soil particles, and drinking water that has traveled through city or home pipes made of lead.

The presence of lead is being detected, particularly within drinking water, at an increasingly alarming rate. A recent GAO report found that nearly half of schools surveyed across the country hadn’t tested for lead in their drinking water within the past 12 months. But of those that did, more than a third found elevated levels.

Many cities have independently been finding significant amounts of lead in their drinking water. An effort within the city of Chicago found that, of nearly 3,000 water samples taken, 70% had lead of some amount and 30% had lead amounts exceeding the EPA maximum allowed for bottled water. Other cities experiencing lead in water issues include Pittsburgh, New Orleans, San Diego, and Nashville. Indeed at the height of this issue occurring in Flint, a reuters report found nearly 3,000 communities with lead poisoning levels higher than those in Flint.

An underlying problem is that we actually don’t know much about the problem.

While the above efforts point to a growing understanding of lead exposure across municipalities, a fundamental barrier with lowering lead exposure—and preventing lead poisoning—is that communities typically don’t know that they’ve been exposed to lead and/or how much they’ve been exposed until it’s too late.

Activists, community and public health experts have difficulty advocating for change because of a root problem: we actually don’t know much about the problem. There just isn’t sufficient data on lead exposure within communities to communicate any specifics around the problem in order to drive some sort of preventative action. Rather, communities are reactionary to findings, rather than strategic in their effort. And public health systems often only kick in after lead poisoning has been documented, not before then to prevent lead poisoning from happening in the first place.

Here’s why.

A major driver of the current system comes down to costs.

It’s fairly expensive to test for lead. The highest EPA standards require the use of ICP-MS which, due to its cost (of over $200,000) and complexity (trained professionals are needed), is only available through professional testing labs and universities.

And if lead is found, it’s even more expensive to address the issue. For example: The Oakland Unified School District recently estimated that it’d cost $38 million dollars to address high levels of lead in the tap water at its schools.

These high cost of completely remediating the issue (such as replacing pipes) is way too high for local health departments. And anything short of complete remediation, such as the very good idea of providing filters to residents so that they can filter their water, leaves a very real feeling of insecurity in residents. The underlying problem is still there.

These forces create a natural disincentive for local leaders to be proactive about this issue: There is little to no ince would they seek to learn more about where lead is and who it is impacting?

Formal top-down efforts and general market and political forces have shown themselves insufficient at addressing this underlying issue.

But a few bright spots show us what’s possible

Meanwhile there are certain localities, institutions, and individuals are at the forefront of this. For example:

The Chicago Department of Public Health, in partnership with University of Chicago, is using various data modeling techniques to better identify which individuals and households are at risk for lead poisoning so that the City can prioritize remediation efforts with those individuals and households. (PDF)

The University of California San Francisco (UCSF) developed a relationship with a high school in Oakland. High School students in a science class collect samples from their homes and neighborhoods and then take a field trip to UCSF where graduate students analyze the samples. (link)

A number of cities have been proactive about finding and replacing lead water pipes in their communities. For example, Tucson, Arizona is in its second year of a Get the Lead Out Program and developed a story map to communicate its efforts to its citizens. (link)

There are also a myriad of policy efforts coming from different levels, including State-level policies which ranges from requiring public schools to test their water sources for lead to increasing requirements for childhood testing for lead among those with Medicaid.

Further, community and citizen scientists have been taking testing into their own hands in order to build the evidence and force their city to address their concerns. Better equipping them with new technologies, and better integrating them with public health institutions has the potential to activate much greater awareness and action.

However, due to the hyperlocal, multi-sectoral, and public health nature of the lead problem, these efforts are fragmented, under-funded, and often secondary to “more pressing” issues that require immediate attention.

Enter: The Lead Data Initiative

This initiative engages and brings together various stakeholders — government, academia, health care, and neighborhood organizations — to help facilitate data gathering and sharing at the local level in order to cultivate and elevate hard conversations that drive critical actions.

Figuring out what this exactly means and looks like is the focus of the first stages of this Initiative. But we think the conversations fall into three different buckets:

Engaging with and across city officials, particularly those that work within lead remediation programs, community development offices, and county-based Departments of Public Health.

Engaging directly with communities most affected by lead and equipping and empowering them to take testing into their own hands, perhaps via local partnerships and/or with low-cost tools.

Engaging directly with engineers and technologists who can help develop lower-cost technologies for the testing of environmental lead exposure.

…

I’m leading this project via a Fellowship role within Public Lab, a non-profit. Funding for this effort coming from Schmidt Futures.

Want to learn more or be involved? Email me or jump into the conversation already happening at: publiclab.org/lead